Welcome

to Johnbirchall-economist.com!

(Leprosy remains

a problem – a brief analysis)

Leprosy, an age old disease closely

associated with biblical times, has not gone away. In fact, about 500,000

new cases - more than 1,400 people every day - were diagnosed in 2005.

In 1996 the World Health Organisation

said it hoped to all but eliminate the disease within 10 years.

But in 2006 people in South America,

Asia and Africa are still living with this debilitating illness even

though a cure, which is available for free, was found more than 20 years

ago.

It is hard to pinpoint why it is taking

so long to eradicate an illness that has not been found in Europe for

decades.

Tim Lewis, a doctor working in Nepal for

the Leprosy Mission International thinks the continued stigma surrounding

the disease could be to blame.

He said: "There is definitely still

a stigma surrounding leprosy. We are still seeing some patients coming at

quite an advanced stage of disease and the main reason why people delay

treatment is still fear of rejection."

"We had one case where a man with

the disease lived with his family, but they drew a line down the centre of

the house and told him to stay on his side. His food was then passed over

the line."

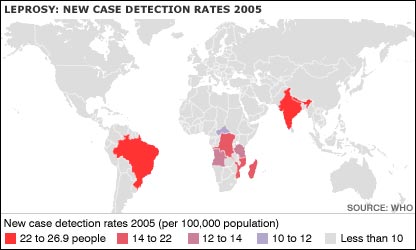

Total

number of new cases in 2005 (Source: WHO)

-

SOUTH

EAST ASIA - 201,635

-

AFRICA

- 42,814

-

AMERICAS

-52,662 (2004 figure)

-

WESTERN

PACIFIC - 7,137

-

EASTERN

MEDITERRANEAN - 3,133

June Nash, a missionary for more than 30

years, has also witnessed first hand the shame a leprosy diagnosis can

induce. She recalled the story of one patient from Africa who thought she

would have to get a divorce after being diagnosed.

She said: "The patient was cured of

the disease and didn't have any disabilities but was convinced she would

have to leave her husband just because of the shame."

Daniel

Izzett, a pastor in Zimbabwe, began losing the feeling in his fingers when

he was a child but was not treated for the illness until he was 24. He

told his immediate family but admits delaying telling anyone else because

he feared their reaction.

"I

was almost living in denial but it was 10 years before I was told I had

leprosy after being continually misdiagnosed.

"I

told my family and my bosses at work because I needed time off for

treatment but generally we kept it a great secret because of the stigma.

It seems an unwritten law in society - fear of leprosy."

Curable

disease

Most

of the worries surrounding leprosy may stem from the fact that it is

probably spread by airborne infection such as coughing and sneezing. The

first outward sign is a patch on the skin, usually associated with loss of

feeling around that area.

However,

it is now thought that 95% of people are naturally immune to the leprosy

bacteria and once a patient begins treatment they are no longer

infectious.

Multi drug

therapy also cures most victims but physical deformities, including

damaged hands and feet, remain. This may make it hard for family and

friends to accept sufferers.

Another

factor which could have added to leprosy's doomed reputation includes the

once prevalent 'solution' of transporting sufferers to leper colonies,

also known as Leprosaria, which were often located on remote islands.

Transferring

patients to these far-away places added to the mythology that the disease

was 'dangerous' according to Ms Nash.

"The

health profession certainly did not help early-on because removing these

people from society simply reinforced the misconceptions," she said.

Most

colonies were closed in the 1960s, when drug treatments began to advance,

but in Japan the last one remained open until 1996.

A

government panel which reported on Japan's health policy towards lepers in

2005 also found that for a period of 30 years, up to at least the 1950s,

the babies of hundreds of patients were deliberately killed by medical

staff.

Some

colonies are still operating in Eastern Europe and India mainly because

sufferers are now used to living cut-off from society and feel safer in

these controlled environments.

Tackling

long held worries about rejection and shame seems key to overcoming the

illness in the long term because the sooner people are treated the less

likely they are to become seriously disabled.

Pastor

Izzett thinks the attitude is changing.

He

said: "My family kept it secret for 28 years before going public but

when I told the church where I am the pastor no-one rejected us. In fact

most of the remarks were 'why didn't you tell us before?'."

The

WHO's desire to eliminate leprosy may eventually be achievable within a

few years but the fight is far from over.

Julie

Lewis, another missionary in Nepal, thinks tackling poverty on a global

level would be a start.

"If

you raised the living conditions of everybody in the world leprosy would

automatically disappear. It disappeared from Europe before a treatment was

available just because people's living conditions improved," she

said.

And in the meantime education and awareness needs

to continue if a world without leprosy, a disease as old as mankind, is

ever going to exist.